This page contains articles on particular recordings and artists, piecing together biographies, history, context and meaning. I also talk about the circumstances of finding each record.

Search Guide: the search box below may produce results tagged to a page, not a specific section. Please use ctrl+f to locate exact words.

Old World Music Classics #29

Nie Zna Śmierci Pan Żywota- Kwartet Braci Okulskich

1929 (Columbia Records)

POLISH-AMERICAN

In the late 1990s in London, when I began to collect shellac, good ethnic 78s were scarce. In the heyday of the technology, the city lacked the huge swells of immigration that convinced New York City record companies to churn out thousands of ethnic titles in the teens and ‘20s. Not long after we moved to Boston in 2005, picking through the crates of random 78s he’d brought along for the ride, I met an old gramophone dealer at Brimfield Antique Market. He assured me that he had a barn-full more back home. “Always only $1 each, even if you find a rarity. I don’t know what’s in there.”

Sure enough, when I arrived at his place in New Hampshire, he showed me to an outbuilding tottering with shellac. Just in the immediate vicinity I spied some dark green Columbias, the livery of the most prodigious ethnic series in American history.

That day I went home with over 80 discs—Irish, Czech, Italian, German—labels and places almost unknown in the UK in the wild.

But it was a random Polish record, a Columbia from 1929, that most caught my attention.

Record label for “Nie Zna sMierci Pan zYwota” by the Kwartet Braci Okulskich (Columbia Records 18308-F, 1929)

Not the harried sawing fiddles on many a CD compilation but a hymn rendered by a sweet quartet and ragged soloist accompanied by bells, gossamer organ and strings. An “Easter Song” (Nie Zna Śmierci Pan Żywota), the piece evoked both simple village faith and Big Apple sophistication. And the performance, tense then exultant, stopped me in my tracks.

I knew nothing of the quartet—Kwartet Braci [Brothers] Okulskich—and quick online searches turned up very little. The track became an enduring favorite, but I put off further enquires for another day.

A full fifteen years later, I finally began some serious research. Despite the span of time, the Internet offered up the same meager results: scattered tracks on YouTube, scant discographical entries, all regurgitating the same basic facts. Spottswood counts a dozen discs under the quartet’s name, two on Okeh and the rest on Columbia, between 1925 and 1929. The early discs included the quartet’s hometown: Passaic, New Jersey.

I turned to genealogical and old newspaper sites, and initially found nothing. “Okulskich” produced almost zero. I then noticed the prior entry in Spottswood: Fabian Okulski. Might this be a member of the quartet recording as a solo artist? References to Fabian—and various brothers—turned up quickly on Ancestry. Then I stumbled on material so often missing when researching little known ethnic recording artists: photographs and a potted family history (written by younger brother William, not a member of the quartet). These documents confirmed that these Okulski brothers were indeed the Kwartet Braci Okulskich.

So here is my pieced together account of the Kwartet Braci Okulskich, seemingly the first time the brothers’ genealogical record has been properly connected to their brief career as ethnic recording artists.

The members of the Kwartet Braci Okulskich were:

- Chester Okula (born 1894)

- Alfred Okula (born 1896)

- Fabian Okula (born 1900)

- Benjamin Okula (born 1902)

The brothers were born in Warsaw in then Russia-controlled Poland, their parents (Joseph Okula and Anna Bielawski, both born in 1863) having migrated from their respective villages.

Within the Russian imperial orbit since the Conference of Vienna in 1815—when much of Europe was reorganized after Napoleon’s demise—Warsaw grew, industrialized and prospered but was never at ease. Periodic demonstrations and uprisings, demanding Polish autonomy, were met with Russian gunfire and repression. Relentless Russification saw restrictions on the Polish language and native Catholicism.

The Russian Revolution of 1905 spilled over into Warsaw and other Polish cities, fueled by recession and imperial disarray after Russian’s surprise loss to Japan in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05. An amalgam of Polish independence and socialist zeal spurred the demonstrators, leading to a long and ugly general strike. The Russian authorities, consumed with tumult at home, teetered between concessions and violence.

Strikes and demonstrations swept the “Polish Partition” in 1905, the year Anna and her four sons fled to America.

This was the backdrop to the Okula family’s decision to try to reach America. Joseph had for years evaded conscription into the Imperial Army, scraping together enough money to pay someone else to go in his place (a legal escape hatch at the time). But with Russian forces bleeding in the east and facing revolution at home, he knew he could evade no longer.

Joseph devised a plan. Through army connections, he arranged for Anna to become governess for a wealthy family, taking the boys with her. The family spent the summer near Odessa on the Black Sea. Then, as Joseph envisaged, his wife and sons fled into nearby Turkey, gradually making their way—on foot and by wagon—into Europe and finally to Rotterdam and the SS Rijndam to New York City, arriving in July 1906. The immigration authorities somehow changed the family’s name from “Okula” to “Okulski”.

Joseph entered the army, stationed in Siberia, but eventually escaped. He somehow reached Ellis Island himself in 1908.

The family lived first in Ipswich, Massachusetts, near a relative, before moving to Paterson, New Jersey, just across the river from Manhattan, in 1914. Musical talent precipitated the relocation: Anna sang and saw promise in her boys, eking out money for music lessons. Alfred at age 13 was organist at a church in Ipswich. A Father Nowakowski from Paterson heard of the musical family and convinced them to migrate, installing Alfred as organist in Paterson’s St. Stephen’s Church. Fabian also learned the organ and piano. Chester took up the violin, Ben the organ, and all four brothers sang.

In 1916, Joseph was killed in a railway accident, hit by a train as his car crossed the track. Fog and a faulty train whistle caused the tragedy. After a legal battle, the family won compensation, investing the money in an ice-cream store. War rationing put an end to that business, and the older brothers enlisted.

After the war, the brothers found employment in the orchestra pit at local theatres, accompanying vaudeville and silent movies. All four married in the teens or early 1920s, continuing to reside in Paterson or nearby Passiac.

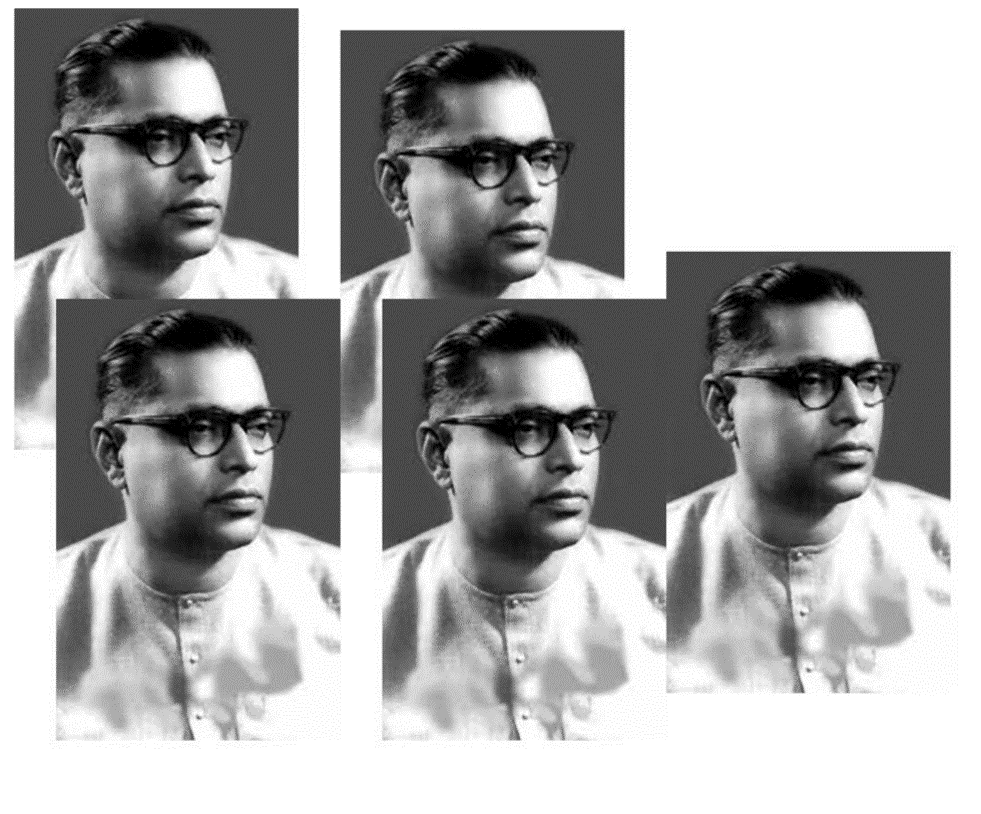

The Brothers Okukski, with mother Anna (1920).

Making Records

In 1925, amid increased commercial interest in ethnic records, centered in nearby Manhattan, the Okulski family’s talents came to the attention of the Okeh record company. The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 curtailed immigration to the United States, drastically reducing the flow of new arrivals from the old county. This put a premium on “authentic” homegrown singing and music. The strong economy of the 1920s gave many first-generation Poles more disposable income, putting phonographs and records within reach. Parallel to growing commercial openness to “down home” blues and country music during this period, the record companies opened the door to a wider range of ethnic styles.

The brothers Kwartet Braci Okulskich, featuring vocals, bells, organ and violin, stood somewhat apart from the usual dance music, solo singers and instrumentalists in the Polish catalog. Twelve discs were issued between 1925 and 1929, almost all with a religious theme. According to younger brother William Okulski’s recollection, some of the pieces came from Anna’s repertoire, some were traditional, and some composed or adapted by one or more members of the quartet.

The records are scarce today, suggesting less than stellar sales. Equally, the brothers’ switch to big-time Columbia Records in 1926 indicates some commercial success- although I can find no advertisements for the records in period newspapers. In the 1920s the family ran a piano store, also selling phonographs and records. Having an in-house quartet with its own line of records must have been a nice fillip for the business. Fabian Okulski convinced Columbia to let him record an additional sixteen solo sides—all Polish material—in 1928 and 1929. His final recording took place a month before the stock market crash.

The Kwartet Braci Okulskich- a Columbia Records publicity shot (c.1926): l to r- Fabian, Benjamin, Alfred and Chester.

The Great Depression chewed up the ethnic recording industry, crushing record sales everywhere. The 1930 census records three of the brothers working as musicians, two in the theater and one as a “musical director”.

Two of the brothers pursued musical careers. William says Alfred attended the Julliard School of Music and Boston Conservatory, composed a mass to St Joseph, in honor of his father, and was a choir director. He led the Harmoni Choir to victory at a Polish Choirs competition in Cleveland in the 1950s. Fabian was a band leader, accompanying shows and films in theaters. He is said to have conducted for stars such as Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor.

By 1940, Chester was a “proprietor” (of rented accommodation or a store?), Fabian an “agent” (likely music-related) and Benjamin worked as a tester of radio sets. Only Alfred listed “organist”.

Both Alfred and Fabian were employed as church organists at the time of the 1950 census. Chester was a painter at the Freight Car Manufacturing Company, and Benjamin was a foreman at an “Electrical Instruments Factory” (and also a church organist, according to William).

Alfred died suddenly in 1961, of a brain hemorrhage, while at home playing the piano for friends. His funeral was attended by over 1,000 people. The other brothers, William included, passed away in the early 1980s.

Easter Song

The Kwartet Braci Okulskich track that caught my attention is a celebration of Christ’s resurrection and victory over death. The words are from a poem by Franciszek Karpiński (1741-1825), a fondly remembered Polish writer of romantic and religious verse. The music appears to be by Teofil Klonowski (1805-1876), a well-known composer of Polish choral music.

Franciszek Karpiński, author of the words to Nie Zna Śmierci Pan Żywota; and a 1905 Easter postcard from Poland.

Here is my translation of the words of Nie Zna Śmierci Pan Żywota:

The Lord of Life Knows Not Death

The Lord of life knows not death

although he passed through its gates;

The tomb was rent.

Holy hand. Hallelujah!

The tomb was rent.

Holy hand. Hallelujah!

Adam, your debt is repaid,

You are reconciled with the nations.

You will enter Heaven with your joyful children. Hallelujah!

You will enter Heaven with your joyful children. Hallelujah!

Vainly you soldiers are guarding!

You will not find him in this grave.

He rose, diffused into the dome.

God of nature. Hallelujah!

He rose, diffused into the dome.

God of nature. Hallelujah!

(based on a translation by Marcin Lydka)

This 1929 recording by the Kwartet Braci Okulskich evokes religious devotion and communal dignity far from home, with the last days of Roaring ‘20s New York City blaring outside. Along with millions of their fellow immigrants, these four young, naturalized Americans straddled old world and new, Polish and English, having pieced together a new life. Like the harmonies of the piece, the brothers found resonance from dissonance. The instrumentation—the flourish before the final verse—speaks to personality and ambition. “Tradition” is never static. Old hymns and sharp suits; holiness and microphones.

Against the odds, the coincidence of ethnic vibrancy and new technology captured the moment before it was lost.

I have yet to find all twelve of the Kwartet’s discs. What I’ve heard so far, from four, are in similar style, but none reach the heights of Nie Zna Śmierci Pan Żywota. Perhaps something else awaits discovery.

Old World Music Classics #28

Baïlèro- Madeleine Grey & D’Orchestre de L’Opera Comique

1930 (Columbia Masterworks reissue 1945)

AUVERGNE- FRANCE

Detail from the cover of the 1945 Columbia Masterworks reissue of “Songs of the Auvergne”.

This track is a vintage rendering of music in the Occitan language from southern France: Baïlèro, from the famous Songs from the Auvergne collection by Joseph Canteloube (born 1879) and sung by soprano Madeleine Grey. The composer managed, with a few notes and words, and Grey’s performance, to propel this song to immortality- if himself to obscurity.

To my ears, Baïlèro is a rare example of composed music inspired by folk tradition that transcends both: more sweeping and lyrical than most field recordings but bright and immediate in a way few “serious” works manage.

A ubiquitous vocal piece today, found on endless light classical selections, Baïlèro was long unmoored from context or intent.

What is the story behind this incredible composition and stellar recording?

Marie-Joseph Canteloube de Malaret was born into a well-to-do family in the Auvergne region of France, speakers of the Auvergnat Occitan dialect. He studied piano as a child, and as a teenager began to compose. He moved away for university and then embarked on a banking career, torn between a life of music and earning a living. When his father died, Joseph returned home to take over the family estate.

But music continued to inspire him and following correspondence with Vincent d’Indy, a noted composer of the time and more than twenty years Joseph’s senior, the young father, leaving his wife and twin sons behind, moved to Paris in 1907 to enroll in d’Indy’s Schola Cantorum, a music academy. Founded in 1894, the Schola Cantorum emphasized older musical forms, such as Gregorian Chant and Renaissance polyphony. D’Indy was a devotee of Wagner, taken with the German’s molding of folk traditions and national pride. The Schola attracted aspiring composers from France and beyond, including many mesmerized by folk music, such as Isaac Albéniz from Spain, a few years before Joseph’s time, and John Jacob Niles from the United States, a few years after.

Joseph gradually made a name for himself as a composer but struggled to align his musical instincts, favoring the strains of his home region, with the tastes of the capital’s elite. His early output, operas, suites and symphonic poems, a pan-European sensibility, gave way to song cycles inspired by the peasant music of the Auvergne and other French regions.

From 1910 to 1925—sidetracked by the war—Joseph labored on his first opera Les Mas, in the Occitan language. The work won the Prix Heugel and 100,000 francs but it took four years to convince one of the Paris opera houses to stage it. A second opera, Vercingétorix, about a Gaulish chief who resisted the Romans, was also tepidly received.

Baïlèro, the star of the most famous Chants d'Auvergne, begun in the mid-1920s, garnered Joseph some attention, leading to the first recording of the piece, along with a selection of other songs, in February 1930.

Timing was fortuitous. The horror of the First World War a fading memory, French nationalism and regionalism bright and vital, and the collapse of the long economic expansion of the 1920s not quite realized, the Songs of the Auvergne 78 rpm album set, as it appeared in English, barely escaped the maw of the Great Depression.

The involvement of Madeleine Grey (1896-1979), the voice that helped push the work into the limelight, was also opportune. A French singer of Jewish heritage, Grey was much admired during the 1920s and worked with leading French composers such as Ravel and Fauré. Joseph sent her a copy of his Chants d'Auvergne, and she gave the compositions’ first public performance in 1926, to great success. Despite acclaim, enhanced by the favorable reception of the recordings, Grey made very few other studio appearances, hobbled by rising antisemitism. If Baïlèro had been recorded just a few years later, Madeleine, credited with rendering a freshness and directness inherent in the music, dimensions others sings may have struggled with, might not have been considered.

Indeed, the conductor on the Baïlèro recording was Elie Cohen, the Jewish Chef D’Orchestre de L’Opera Comique, which accompanied Madeleine Grey.

Madeleine Grey, singer on the first recording of “Songs of the Auvergne”.

To me, Baïlèro is very striking, capturing a joyous essence both ancient and composed. Yet the rest of the song cycle, at least what I have heard on the original and subsequent recordings, pales by comparison: so much quotidian cheeriness and tame thematic recycling. My ears recall endless dull field recordings of folk music the world over; evocative sepia photograph album covers, quaint and worthwhile, drawing me in, aching for some magic. Sitting outside the culture, the words, the local color, uncertain in translation, seem at best mysterious and at worst banal. Without Baïlèro, I wonder if Chants d'Auvergne would be long forgotten.

To add to the miracle, the words of Baïlèro, at least in English, seem trifling: a conversation with a shepherd—whose calling to his sheep is the song’s signature—exchanging clipped remarks about the troubles of pastoral life, where the grass is best and the river between them. The personality of the singer (simply a “girl” according to some commentators) is unclear.

Shepherd across the river,

You're hardly having a good time,

Sing baïlèro lèrô

No, I'm not,

And you, too, can sing baïlèro

Shepherd, the meadows are in bloom.

You should graze your flock on this side,

Sing baïlèro lèrô

The grass is greener in the meadows on this side,

Baïlèro lèrô

Shepherd, the water divides us,

And I can't cross it,

Sing baïlèro lèrô

Then I'll come down and find you,

Baïlèro lèrô

Perhaps it is a shy love song or makes subtle allusions to the urban-rural divide, but any deeper meaning appears lost. Baïlèro, today a minor staple of the “classical” repertoire, present on innumerable “relaxing classics” collections, has assumed a life of its own. The song’s regional origins are acknowledged but nothing more, with Joseph noted only in passing.

"Peasant songs often rise to the level of purest art in terms of feeling and expression, if not in form." Like many folklorists of his day, Canteloube transcribed the music he heard from the mouths of the people. He did not employ the phonograph, then used by a few collectors since the 1890s. The composer is quoted as saying that a transcribed folk song "is like a pressed flower, dry and dead - to breathe life into it one needs to see and feel its native hills, scents and breezes". Joseph saw adaptation and orchestration as that breath of life, the recreation of the sounds of home, but it would be fascinating to be able to hear the source for Baïlèro, if there was one.

To my ears, field recordings from Auvergne and of Auvergne extraction in Paris—such as the those on the France- Une Anthologie des Musiques Traditionnelles CD boxset released in 2010—sound pedestrian by comparison. This suggests either that what Joseph remembered from his youth had vanished by the time a recording device showed up, or that Baïlèro is predominantly the product of the composer’s study, passion and imagination.

During World War II, Joseph cooperated with the Vichy regime, broadcasting French folk song recitals on the radio. Given the vicious nationalism of the Nazis, perhaps this was quiet subversion.

Joseph Canteloube as a young and older man.

As Joseph faded into old age and obscurity, “Songs of the Auvergne” took on a life of its own. Remarkably, strains of Baïlèro ended up in William Walton’s music for Olivier’s 1944 film of Henry V, a British blockbuster designed to boost morale late in World War II. That French regional music was chosen as the backdrop for a tale of the English bashing the French underscores the raw appeal of Baïlèro. The piece provides the crescendo at the wedding of Henry and his bride, Catherine, daughter of the vanquished French king.

After the war, Joseph continued to tinker with his most famous work, expanding Songs of the Auvergne to five volumes. He died in 1957.

Much folk-inspired art music stumbles while Baïlèro soars, tethered to the soil but flashing high above it.

Old World Music Classics #27

Processo de Saint Bartomeu- Cobla La Principal de La Bisbal

(Disque “Gramophone”, 1931)

CATALONIA- SPAIN

For the record collector, the most precious quarry is a disc of delightful music that nobody wants. Norms dictate which records are desirable, expensive and hard-to-come-by and which are dismissed, cheap and ubiquitous. But sometimes orthodoxy overlooks something.

So it was when a well-known dealer in Paris listed a host of delectable international 78 rpm discs on eBay- among them dark choral dirges from Albania and lusty theater troupes from Madagascar, genres highly prized in the world of ethnic shellac collecting. But also available were a few hard-to-discern discs from Spain, dating from the 1930s; in wonderful condition but priced at a discount.

I took a chance, suspecting either staid classical fare or some gleaming but insubstantial popular style. What I discovered, weeks later when the thick cardboard box arrived, a straitjacket of tape and padded with crumpled French tabloids and supermarket coupons, was some remarkable music.

Several sides caught my attention but most exuberant was La Processo de Saint Bartomeu by the Cobla La Principal de La Bisbal.

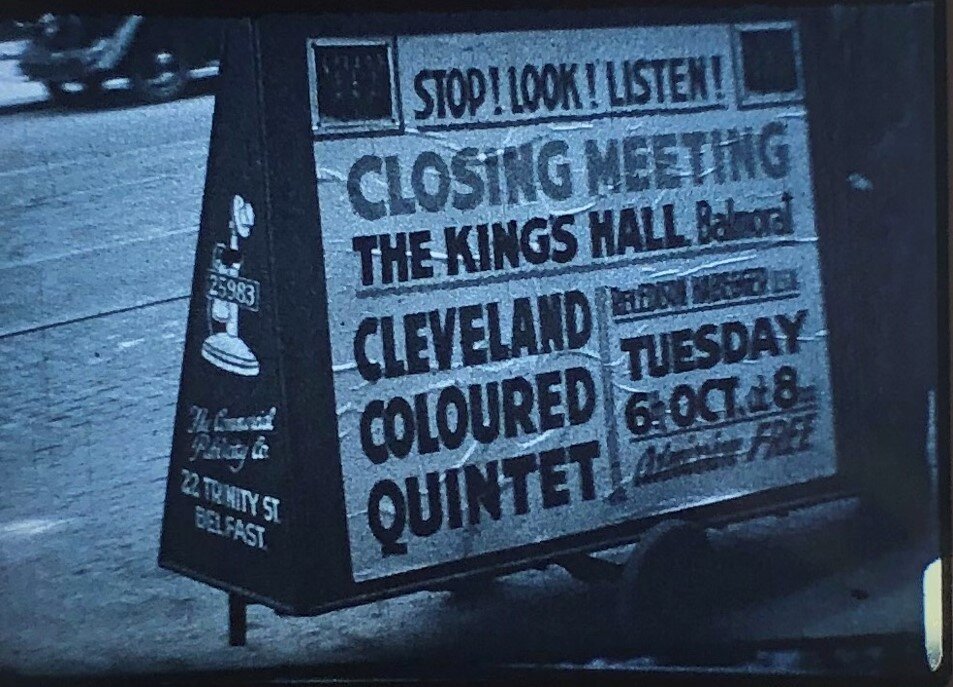

La Processo De Sant Bartomeu- Disque Gramophone K-4122 (1931)- label

This piece is an instrumental accompaniment to a Sardana, a popular circle dance from Catalonia, the northeast region of Spain of which Barcelona is the capital. Like many regional dances the world over, the Sardana is a mix of distant folk origins and nationalist revival. Josep Maria Ventura i Casas (1817-1875), a composer who was part of the Renaixença, or Catalan cultural renaissance of the 19th century, was taken with local musical forms but sought to develop them. He considered the standard dance and accompaniment too limited- a fixed 98 measures, barely two minutes in length and played by four musicians: bagpipes, shawn (a primitive oboe), and a one-man flabiol (a Catalan flute) and tambori (a small drum).

Josep expanded the ensemble, which gradually evolved to the eleven musicians considered standard from the late 19th century, and the size of the assembly that made the recording discussed here. A larger woodwind section featured, as well as brass instruments and a double bass. The composer also invented the long sardanes form and wrote hundreds of compositions, long and short.

Coblas, groups of sardana musicians, proliferated across the region, conjuring the soundtrack to Catalan nationalist sentiment. The goal was both musical revival and innovation, fashioning new sophistication from hand-me-downs. Music professors and conservatories joined the movement, as well as municipal orchestras.

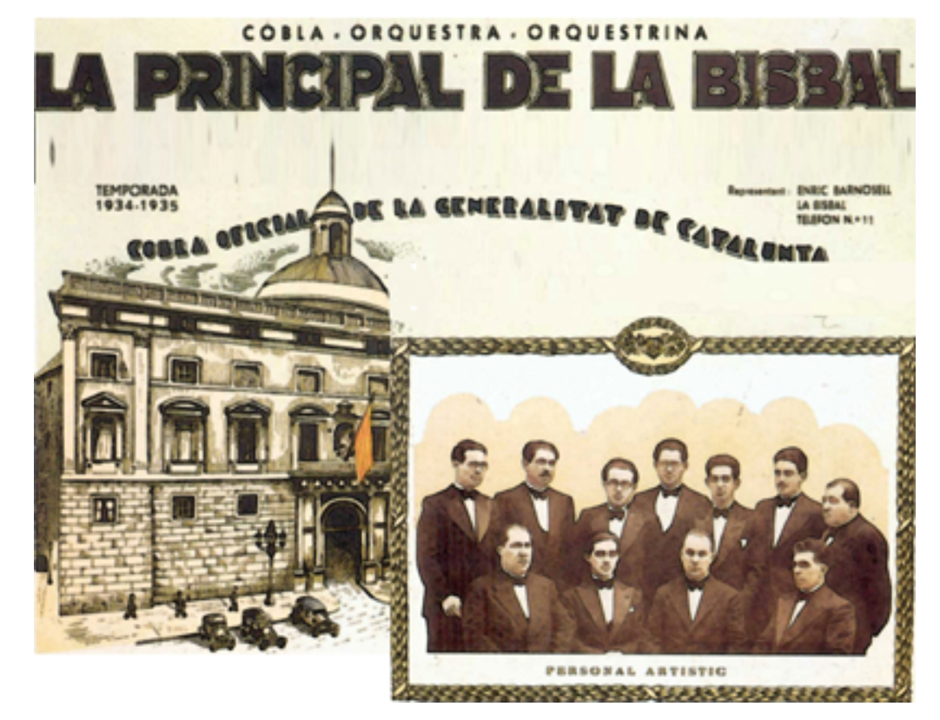

Cobla La Principal de La Bisbal (1934)

Sardanes dances were viewed as both skilled and popular. Tradition dictates that observers may join the circle if so inspired. The braiding of culture and participation, legacy and spontaneity, underlined Catalan claims to ancient nationhood and engaged both ambitious musicians and ordinary people. Catalan nationalists such as the famed poet Joan Maragall i Gorina feted the sardanes as an example of warm, vibrant popular art in contrast to “cold” and over-thought high culture.

As Spain steadily lost its empire and the central government weakened, the regions grew restive for greater autonomy. Advocates for self-determination called for a federal Spain or a Catalan nation rising from Spanish ashes. In 1892, the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s voyage to America (remembering that the Spanish crown sponsored the venture and that some Catalans claim Columbus as their own), Catalonia held cobla contests as part of the celebrations, further disseminating the genre. This year the Bases de Manresa, a founding document of Catalan autonomy, was formulated.

The Cobla La Principal de La Bisbal (CPB), the cobla that made this record, was formed in 1888 in the city of La Bisbal d’Empordà, north of Barcelona. Over the years, a revolving door of 11 musicians formed the core, with singers and dancers added for certain performances.

Joan Carreras i Dagas (1828-1900), composer and musicologist, ran a music school in the town that attracted promising musicians from across the region. Dagas also had a history of organizing “primitive” music schools for local children. He is credited as a guiding hand in the formation of the CPB. As the waves of sardana and Catalan feeling crested, the CPB, like comparable ensembles all over Catalonia, was a vehicle to showcase and evolve indigenous composition and musicianship.

To my ears, the music of the CPB and similar coblas is both familiar and strange. Quotidian trumpets and double-bass mingle with two tible and two tenore- smaller and larger shawms that make tight, buzzing blasts- two fiscorns- a rotary-valve baritone saxhorn with the bell facing forward- a valve-trombone as well as the one-man flabiol (a tiny one-hand piercing flute) and tambori (small drum, tapped with a stick or one finger) player.

Cobla La Principal de La Bisbal- 1920s?

Some cobla pieces meander, imitating long-winded classical forms. The restricted span of the 78 rpm recordings I have heard often mean extra focus and energy. From the first trill of the flabiol, many of the recordings are endlessly immediate, rousing and inventive.

This particular piece, La Processo de Saint Bartomeu, recorded in 1931, is not credited and is most likely a traditional composition that has been adapted over the years. Bartholomew was one of the twelve apostles of Jesus and was martyred somewhere on the outskirts of eastern Christendom, skinned alive and crucified upside down according to legend. I can find no obvious connection between Bartholomew, La Bisbal d’Empordà or the CPB other than the saint’s feast day being a fixture on the Catholic calendar (August 24).

I imagine the musicians, sweltering in their Sunday best, up on a platform as the townspeople file past holding aloft some minor relic of the saint.

CPB operates to this day. The ensemble has always blurred the lines between Catalan and international fare, and traditional and modern. The most prominent videos online show recent incarnations performing the Rocky theme and singing songs from West Side Story, but pieces similar to those captured on old recordings are also in evidence. In fact, the “cobla” outfit appears to stick with traditional pieces while offshoots do show tunes, Frank Sinatra and other fashions. Recent cobla videos, filmed in town squares, show many audience members dancing in large, informal circles- bags and coats piled in the middle.

I later remembered that two CPB pieces closed the 1996 “Voice of Spain” CD on the Heritage label, a retrospective of Spanish regional 78s reviewed in The Gramophone magazine by diplomat and musicologist, Rodney Gallop. I bought this CD in 1997, opening my ears to styles I did not know existed.

For a video version of this track—the music accompanied by commentary and period photographs—please click below for a link to my Music Atlas YouTube channel.

Old World Music Classics #26

Palesteena- Original Dixieland Jazz Band

(Victor, 1920)

JAZZ- USA

Much early jazz- pre-1925- I find dull. The energy and excitement of the music, so exhilarating or even shocking to contemporary ears, can seem tame today. So much form over substance, all speed and novelty. And the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, first to make jazz records, and forever bedeviled by being in both the right and wrong place at the same time, epitomize the problem. Titilating audiences with their frenetic syncopation, this white band from New Orleans are often dismissed as just the lucky jokesters who cleared the way for the real thing.

I found this record in an antique market on the outskirts of Denver, Colorado. Shiny as new, and just $2. I knew the significance of the band (years ago in Bedford, UK, as I waded through tottering piles of 78s, the owner winked “All just £1 each, unless you find any Original Dixieland Jazz Band records”), but I was not expecting much. The A side, Margie, has a nice chord change but is otherwise forgettable. Side B, however, made me sit up and pay attention. Here, in 1920, was a piece of obviously carefully composed jazz, as much for listening as dancing, and evoking not the streets of the Big Easy but the Jewish Lower East Side. Right down to the ten second clarinet solo in the middle, stopping the dancers in their tracks, as if Naftule Brandwein or Dave Tarras had joined the band.

Record label- Palesteena by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band (Victor Records, 1920). Composed by J. Russell Robinson and Con Conrad.

What was this music? Appropriation, parody or genre-twisting, stereotype-crunching creativity?

Let me first offer an opinion on the rumbling ODJB controversy- mediocre opportunists who took advantage of racist times or under-appreciated pioneers with a fleeting edge over their peers?

The ODJB did indeed strike gold when they made the inaugural “jass” records for Victor in 1917, sparking a worldwide craze that revved up the Roaring ‘20s. At that early date, the musicianship and originality are unarguable, and the music was fresh and exciting. The heart of the matter- whether ODJB really did come up with the formula of timing and interplay that marked “jass” as something new, as they always claimed, or whether they were just the first to etch a regional sound on shellac- can never be answered conclusively. By definition, no earlier jazz records exist, and efforts to find such- from James Reese Europe to Wilbur Sweatman- never quite match or transcend the ODJB sound, or are mythical, such as the supposed Buddy Bolden cylinder.

New Orleans was a hot bed of musical possibilities, with strong African American influences, yes, alongside numerous European, Caribbean and Creole strains. The fact that jazz arose in that city strongly suggests that it was the diversity of musical contributions that shaped the new sound. That children of European immigrants should be part of the jazz story seems logical, and there is no denying that numerous Big Easy residents of European extraction played in the city’s array of brass, string and ragtime combos in the first years of the 20th century, and that music drew inspiration from far and wide.

Left- a photograph- used to great effect in Ken Burn’s Jazz documentary- emblematic of more fluid color lines in early 20th century New Orleans. Right- a pre-World War I band led by “Papa Jack” Laine- center- said to have recruited musicians, including Nick LaRocca, from every section of the city.

The trouble was that the Original Dixieland Jazz Band struggled to evolve. Torn between riotous numbers, “authentic” down home blues, and Tin Pan Alley standards, the ODJB never found a mature voice. Overtaken by imitators and innovators alike, jostled by the “symphonic jazz” of Paul Whiteman and George Gershwin, the blues fad that added suggestive lyrics to jazzy instrumental gyrations, and by the step-change small band creativity of Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet, the band were running on empty by the mid-1920s, and broke up. A flitting 1930s revival aside, Nick LaRocca, cornetist and band leader, then spent decades sulking about what might have been, embellishing the tale to the point that he and his bandmates alone had pulled jazz out of the air.

The Original Dixieland Jazz Band at the height of their fame c.1918. This shot captures the band’s dual identity: musicianship and novelty.

The 1960 book The Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band by H. O. Brunn, published just before La Rocca’s death, makes the cornetist’s (often convincing) case but the almost complete lack of recognition for black musicians leaves a bad taste in the mouth. For anyone to assert that the ODJB somehow invented jazz out of nothing- which LaRocca and Brunn often flirt with- is preposterous, but to deny the band members’ formative experiences, skill and creativity is no less far-fetched. If LaRocca’s perspective and humility matched his blowing he might have secured the central place in musical history he craved.

The 2015 documentary, Sicily Jass: The World’s First Man in Jazz directed by Michele Cinque makes LaRocca’s case in more measured tones, acknowledging his bitterness and racism but also his skills and innovation, and that of the ODJB.

There is a piognant moment in the film where three members of a reimagined brass band, assembled in the ruins of the Sicilian town LaRocca’s parents left in 1877, step away from their fellows and join a five-piece jazz band. That jazz has multiple roots, not least from Europe, is the assertion, underlining LaRocca’s contention that the creativity of he and the ODJB was as important as any. A clip of Mark Beresford, famed jazz record collector, playing a tape of Nick LaRocca, later in life, conjures the voice of a working class son of immigrants, challenging the simplistic “white” label with its implications of privilege and blandness. The ODJB certainly had privileges not available to black musicians, but that does not mean white musicians of the period had uniform experiences or lacked inventiveness.

Left- the 1960 book The Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band that made Nick LaRocca’s case as the “creator of jazz”. Right- the 2015 film Sicily Jass that- more subtly- attempts the same argument

I can only smile at the story that Freddie Keppard, black New Orleans virtuoso cornetist, born the same year as LaRocca, turned down Victor’s 1915 offer to record, variously said to have dismissed the fee or be anxious that recordings would enable rivals to steal his style. And smile some more that in January 1917 Columbia Records decided not to issue their (very first) recordings of the ODJB, fearing public backlash at this outlandish music, whether played by whites or blacks. This pushed the band into Victor’s arms who released the first jazz record a few weeks later. The story of the first jazz record could have been very different.

It is a shame that the film Sicily Jass did not feature more black voices. Only one black person is interviewed about the ODJB, and this brief segment is simply used to imply unthinking black incredulity about any significant white roots of jazz. The film is well done and makes a decent case but largely talks to itself.

If we need a reminder of the multiple strands of jazz derivation, Palesteena is a case in point.

Palesteena was composed by Joseph Russell Robinson, a member of ODJB’s second line-up. Original pianist, Henry Ragas, died of Spanish Influenza in 1919. Robinson, born in Indianapolis in 1892, a sometime ragtime composer, theater pianist and songwriter, then in Manhattan, auditioned to replace Ragas and got the job. The band whisked off to London for an extended tour. Back in the states, the ODJB released their only pieces composed by Robinson- Margie and Palesteena, in 1920. The record was a hit, but Robinson maintained only intermittent connection with the band from then on. As their fame dwindled, Robinson turned out a steady stream of compositions for other artists, including Mamie and Bessie Smith, collaborated with W. C. Handy and Noble Sissle, and worked as a session musician. The ODJB’s subsequent records before their demise returned to the Dixieland formula.

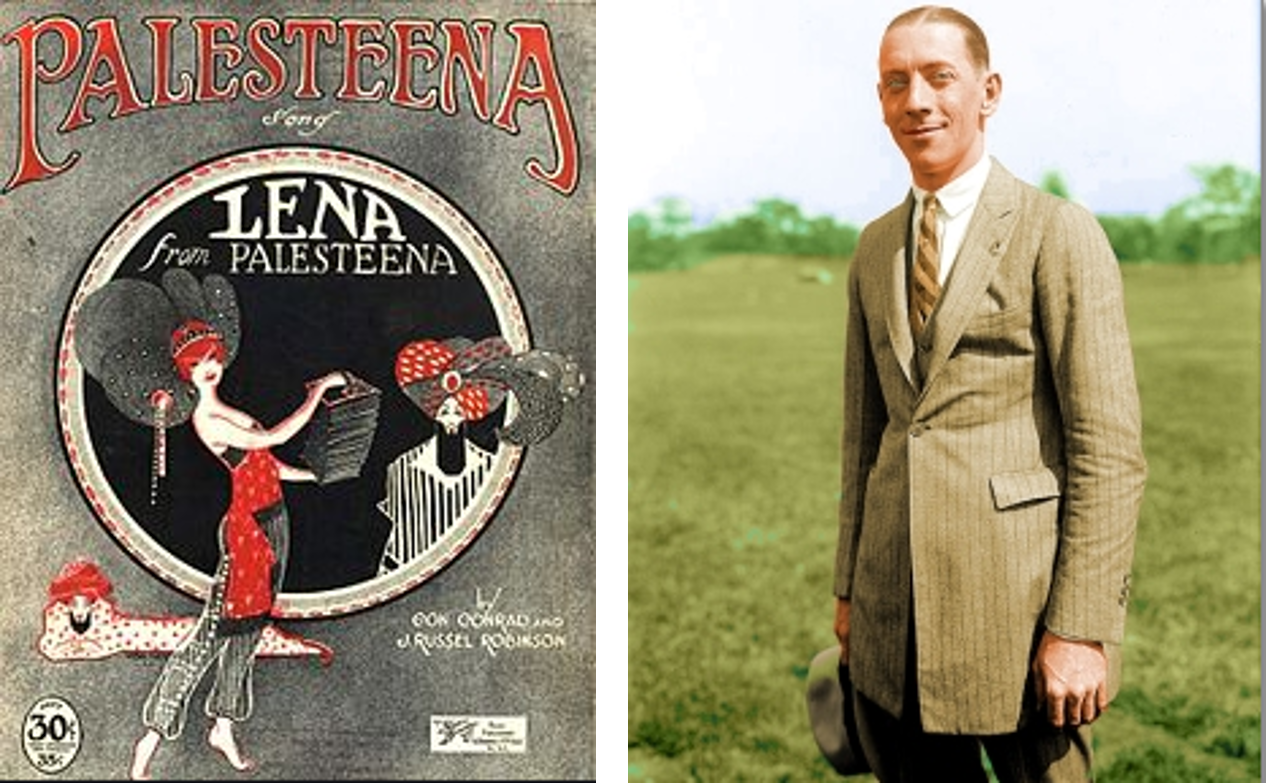

Left- sheet music for the song Leena from Palesteena. Right- J. Russell Robinson, composer of Palesteena and ODJB member at the pivotal moment in their history.

So how to make sense of Palesteena?

The piece has a dual identity- as the ODJB instrumental and a comic song- Lena from Palesteena. It appears the latter, which tells of chubby Lena, a Jewish girl from the Bronx who travels to Palestine to play the concertina (badly) but nonetheless stays trim and entertains the locals, came first. The song- along with Margie- was written with Con Conrad, another aspiring composer. In 1921, major stars Eddie Cantor and Frank Crumit covered the song, reviving the hit over and over.

To my ears, the comic version, with words, has nothing of the elegance and sparkle of the instrumental. The tune is the same but in the vocal rendition is just a vehicle for the lyrics.

From one perspective, the Lena from Palesteena version fits a type of Robinson composition: music clothed in the regional or exotic. Hawaii Calls from 1916, You Brough Old Ireland Back To Me from the following year, and Shanghai Melody and Pan Yan (and his Chinese Jazz Band) from 1919 suggest Robinson saw popular appeal in the allure of distance lands, homeland nostalgia and pocking fun at stereotypes.

So did the songwriters simply start with some lighthearted parody, and then Robinson, perhaps under pressure to give his new comrades, the ODJB, a new twist upon their return to America, spun the sophisticated instrumental?

Regardless the “Palestine” theme was timely. Robinson’s song coincides with the burgeoning settlement of Jews in Palestine, and efforts by the nascent Zionist movement to persuade the British to establish some sort of Jewish homeland in the wake of the Ottoman Empire’s retreat. Robinson’s stay in Manhattan would have exposed him somewhat to the concerns of NYC’s swell of Jewish immigrants. Jews who chose America were sometimes dismissive of Zionist ambitions in Palestine, perhaps inspiring the songwriters.

It may be no accident that Palesteena appeared in the wake of the runway success of The Sheik, the 1919 novel by Edith Maude Hull, which kicked off the “desert romance” genre and sparked a brief period of popular fascination with what we now call the Middle East. Arab love interest and “all those sheiks” appear in Robinson and Conrad’s lyrics.

But Palesteena is more than Arab exoticism or Gentile humor about Jews. In Klezmer: Jewish Music from Old World to Our World, Henry Sapoznik notes that the composition “used the minor-key section of the popular klezmer melody “Nokh a Bisl” (Just a Little More) as its main theme and, in case the ethnic origins weren’t clear enough, inserted sixteen measures of the ubiquitous Jewish melody “Ma Yofus” as a bridge” (p77). This implies Robinson and Conrad had more than an acquaintance with contemporary Jewish music.

While jazz was not recorded until 1917, some Jewish dance music was, and waxed in New York City. Most recorded Jewish music of the era was either Yiddish Theater pieces or Cantorials, but some popular instrumentals and instrumental-backed songs were also made. Abraham Elenkrig’s Yidishe Orchestra recorded twenty sides between 1913 and 1915, and Joseph Moskowitz’s cymbalon discs, some which were Jewish is character, sold well-enough to persuade Victor to issue a string in 1916. Abe Schwartz (Yiddisher Orchester) and Henry Kandel made numerous records, but first in 1917, a few months after ODJB, although both had released plenty by the time Robinson and Conrad penned Palesteena.

In summary, the significance of Paelsteena is twofold. First is that this lone recording, overlooked in the ODJB’s catalog, belies Nick LaRocca’s sour assertion that he alone created jazz. Robinson’s instrumental version of Palesteena is an acknowledgement of the interlaced roots of klezmer and jazz, highlighting just one of the strands that influenced the latter. The tale is told, again by Henry Sapoznik, that renowned Jewish clarinetist, Shloimke Beckerman, was working in another band at Reisenwebber’s restaurant the night in 1917 the ODJB’s debuted in NYC. Years later, recalling seeing the ODJB perform for the first time, Beckerman said “Every trick he did I could do better!” (p101). There is no “original”, just the endless interplay of influence and creativity.

Left- Shloimke Beckerman, the Jewish musician who aged 33 heard something familiar when he saw the ODJB perform in Chicago. Right- fellow pioneering Jewish clarinetist, Naftule Brandwein, and colleagues.

The second reason why Palesteena is significant is that it marked a turning point in the ODJB’s career. The band’s UK recordings already exhibit departures from the frenetic Dixieland mold- some slower, more tuneful numbers; and while Robinson is not credited as composer on any, my theory is that his influence was decisive. Fresh from their England triumph, the band returned to America buoyed with pride and anticipation. But the idea that they could simply repeat their past performances and sustain the same level of success was a mirage. Like any artist, initial popularity requires further innovation to keep audiences engaged and outwit the competition. With Robinson on-board, both Margie and Palesteena afforded ODJB the makings of a new direction, a nod to mainstream dance music and the strains of a multi-ethnic American populace, and most importantly, in Palesteena, creative composed music that took disparate elements and fashioned something new.

But the moment was lost. No doubt LaRocca resented being out of the limelight and insisted the band return to their signature sound. Robinson may have felt underappreciated and saw better opportunities elsewhere. Marguerite, Robinson’s beloved wife and no doubt the inspiration for Margie, died suddenly in 1921, throwing the composer into turmoil. For a few more years the ODJB churned through another series of increasingly outmoded numbers before giving up the ghost.

A young Louis Armstrong who took jazz to new heights in the 1920s. In his biography, Armstrong credits the ODJB, and Nick LaRocca in particular, as an influence. It is a shame that LaRocca could not return the compliment.

Transcending the tired black versus white debate about the origins of jazz, Palesteena is a reminder of other sources and of individual creativity. Had the stars aligned, the ODJB could similarly have transcended their fateful beginnings.

Finally, here is my video version of Palesteena on my Music Atlas YouTube Channel.

Old World Music Classics #25

Skin Game Blues- Peg Leg Howell

(Columbia, 1927)

COUNTRY BLUES- USA

“When I came to Georgia, money and clothes I had babe. All the money I had done gone. My Sunday clothes in pawn”. These are the opening lines of Skin Game Blues by “Peg Leg” Howell, recorded in November 1927. I selected this song for two reasons. First because it is a striking combination of blues sentiment with non-blues melody and structure, a reminder of the tangled influences on blues and country artists at the time, and a far cry from the plodding blues norm. Second because Peg Leg Howell, born Joshua Barnes Howell, is from my current hometown of Eatonton, Georgia.

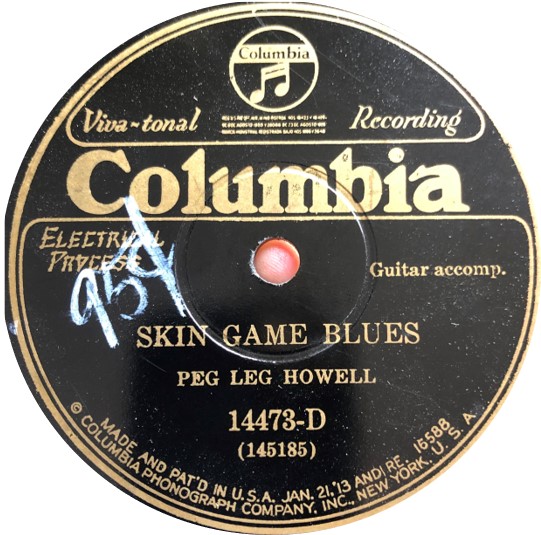

Record Label- Skin Game Blues by Peg Leg Howell (Columbia, 1927)

Biographical sketches uniformly begin with Howell’s birthplace, but the pioneering singer is completely unrecognized in the small southern city he called home. It is ironic, but perhaps typical, that such a town, where segregation is a living memory, should in its search for relevance and viability so conspicuously overlook one of its renowned African American sons.

(Update: in 2022, three years after I published this article, plus a sketch of Howell’s life in the Eatonton Messenger, the City hosted the inaugural “Peg Leg Howell Blues Festival”).

In Eatonton it is Joel Chandler Harris, famed chronicler of the Uncle Remus slave folk tales, who is the most feted local forebear. Depictions of Brer Rabbit, both from the books and the 1946 Disney version Song of the South, dot the city, and there is an Uncle Remus Museum. Mr. Harris died in 1908.

Another famous author, Alice Walker, born 1944, best known for the Pulitzer prize-winning novel The Color Purple, grew up in the surrounding countryside. The legacy of Jim Crow, and Ms. Walker’s vocal criticism of the sometime vicious small mindedness of many white southerners mid-century, meant Eatonton never whole heartedly embraced her, and the feeling was mutual.

This year was Alice Walker’s 75th birthday and there was something of a rapprochement. A gutsy Georgia Writers Museum was established in town a few years ago, with recognition of Walker at its heart. Certain friends and colleagues of the writer saw an opportunity for reconciliation. Ms. Walker at first said that she appreciated the birthday gesture- a weekend celebration was planned- but would not attend. She then changed her mind and was guest of honor. We had the good fortune to host Alice and her party for lunch at the Dot2Dot Inn.

On her website, Alice Walker commented:

Thank you, and blessings to the sweet people of Eatonton, Georgia, from around the country, and around the world, who showed up in loving ways for this amazing celebration. Let it be known far and wide that we have- together, this time- begun the dance of Life again. -AW

My hope is that the reset relationship between Alice Walker and Eatonton grows and develops from here.

But Peg Leg Howell is stuck in the middle. Uncomplicated in death like Mr. Harris but out of public consciousness, unlike Ms. Walker.

Born March 5th 1888, Howell’s documentary mark is slight. I can find no birth certificate online- only in 1919 did Georgia centralize things- and there is no sign of the family in the 1890 census. In the 1900 count, our subject, aged 12, reported as Barnes Howell and still living in Eatonton, is named as a “boarder” with a Rose Bailey, a “washerwoman”. Barnes is “at school” and literate. Perhaps the boy’s parents farmed in the countryside and sent him to a school in town. But no other Howell is reported in Putnam County beyond the city limits.

Four other Howells are named in Eatonton that year- Edward W. Howell, born 1872 and his wife S. Fannie Howell, born 1867, plus their infant daughter, Frances; and an older man, Isaac Howell, a boarder elsewhere in the city. Were Edward and Fannie, Barnes’s parents? Just possibly- although only a surname connects them; but if so, why would their son board nearby?

Howell’s own reminiscences when he was rediscovered in 1963 recalled a farmer’s life in Eatonton until around 1914, working with his father. He then said he worked in a fertilizer factory in nearby Madison before, in 1916, he lost his right leg to a gunshot wound inflicted by his angry brother-in-law (motive unclear). The story goes that Howell, now less able to work the farm or factory, idled around Eatonton before trying his luck in Atlanta, about 75 miles away, in 1923.

Map of North Georgia (1910), showing Eatonton and Atlanta. Taken from the Hammond International Atlas.

Again, our friend is missing from the 1910 and 1920 censuses. A 1917 draft record confirms a Madison address and a lost leg rendering him unfit for military service. The document appears to give his occupation as “nothing”- perhaps Howell’s sore response so soon after the accident. He is married but has no-one “solely dependent” upon him.

Barnes Howell World War I Draft Registration Card (1917)- stating that Howell was married, unemployed and unfit for military service.

Implausibly, Howell claimed he learned the guitar one night around 1909. “I learnt myself- didn’t take too long. I just stayed up one night and learnt myself” he maintained to the young blues enthusiasts who tracked him down in old age. But there is no question that for a disabled black man in the Jim Crow South, musicianship offered a measure of dignity and independence.

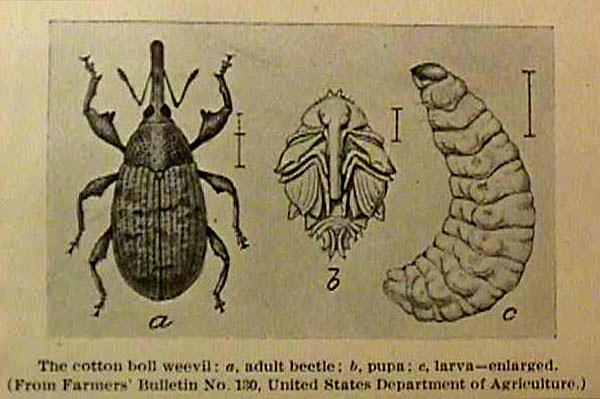

Swelling Atlanta trumped tottering Eatonton, hit hard by the boll weevil scourge in the late teens and early ‘20s. There was far greater opportunity to play for tips on the busy streets of black and in pockets prosperous neighborhoods of the state capital. Howell conjured a mix of a blues and country dance tunes, sometimes teaming up with fiddlers and mandolin players. Playing alone did not pay the bills, persuading Howell to run bootleg liquor- of course illegal under prohibition however you looked at it- which landed him in prison.

No doubt there were plenty of black country musicians plying their trade in 1920s Atlanta, but a Mr. Brown from Columbia Records saw Howell playing on the street and invited him to make a record. This was 1926 when the female blues singer craze was fading, the economy was booming, electrical recording was brand new and record companies were seeing early success with rougher blues, country and ethnic sounds. Billed as Peg Leg Howell, Barnes was the first country blues musician to make a record for Columbia, one of the two leading companies of the day. Howell pre-dates greats such as Charley Patton, Blind Willie McTell, Son House and Tommy Johnson in the studio, and helped the country blues go mainstream (if short-term only within the “race records” market).

Over the next two and a half years, Howell made about 15 records (30 sides) of blues and country music, sometimes solo and sometimes with Eddie Anthony (fiddle) or Jim Hill (mandolin). He was born earlier than almost all other country blues musicians who made records, connecting him to a deeper repertoire.

Advertisements for Peg Leg Howell records in the Richmond Planet (Virginia), 27 July 1929 (left) and 7 July 1928 (right).

Howell’s records are a mix of gravelly complaint about prison life, dangling sexual prowess and pleading for his woman to come back. The country dances are lighter, with playful, rambling lyrics. In my opinion, Howell’s recordings are raw and authentic but few are inspired. The words may be heartfelt, but the tune and playing often routine. If you are not at a country picnic in 1927, the dance music can seem a little over-familiar.

Skin Game Blues stands out. Stefan Grossman, an accomplished guitarist and teacher who learned from a number of blues legends in the twilight of their careers, considers the melody “unique in the history of the blues”. Wilifrid Mellers, in his 1963 book Music in a New Found Land, writes that the “beautiful tune preserves much of the pentatonic freshness and lyricism of Appalachian folk-song from which it is derived; and that tune in turn descends directly from an Irish or Scottish original” (p268). Mellers does not speculate further about the supposed origin of the tune, and I can find no other origin theories. In the notes to the 1960s LP of Howell in his dotage, the singer implies that he wrote the song himself (yet credits third parties for certain other of his records).

A melodic and lyrical cousin may be Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down by Charlie Poole and The North Carolina Ramblers, according to a 1999 Inside Bluegrass article, but the relationship is distant at best. Most likely Howell’s piece, in common with most of his repertoire, is a hybrid of various sources and his own creativity. Reference to gambling “all through Spain” is a giveaway for recycling old lyrical staples. Howell lived all his life in Georgia. He did not “come to Georgia”, as the song maintains.

The melody of Skin Game Blues, free from the clutches of the blues scale, builds the tension, as the second and then surprisingly the third line rises ever higher. As Meller notes, the brightness of the pentatonic scale clashes with the mournful words, and it is this ambivalence that makes the song great. The accompaniment is more rhythmic and banjo-like than a typical blues of the period. Howell recounts his gambling highs and lows, telling his woman what went wrong. He does not make excuses. His tone is repentant.

If this Peg Leg Howell discography is accurate, Skin Game Blues was recorded in November 1927 but not released until 1929. Indeed, it was the b-side of Howell’s final solo record. It is sobering to think that the track might not have been released at all, judged insufficiently commercial or ending up on the wrong side of the stock market crash.

“Skin” is a game, common across the south at the time, where each player is dealt a card and then wagers which like card- another ten or Jack, say- will be drawn first or last, with endless variations. A losing player can try to recoup their losses by selecting another card from those already turned. For a price, a player may select the card of their choice, buying into superstition about lucky cards. The dealer plays against everyone else, inviting all manner of suspicion and trickery.

In her 1935 book Mules and Men, folklorist Zora Neale Hurston describes a game of Georgia Skin. The banter is thick and fast, such as:

From Zora Neale Hurston’s Mules and Men (1935) p146.

Hurston recounts how the dealer sings “Let the deal go down, boys. Let the deal go down” as the cards “fall”, each line punctuated by “hah!” Howell’s song has the same refrain, but his tone is anything but jovial. He dramatizes bold plays- “Hold the cards! A dollar more the deuce beat a nine!”- but otherwise his is a tale of folly. All his money is gone, the police try to arrest him and his fellow players rough him up.

Why “skin”? It is not clear, but perhaps an allusion to fleecing punters.

Skin Game- Florida, 1941. Taken from Shorpy- The Historic American Photo Archive. Used with permission.

Howell’s records sold well enough- more than 10,000 copies in some cases- to keep him busy in the studio. He relays that he earned $50 for his first record, plus unspecified royalties. But everything came crashing down when the economy tanked in 1929. Before long, Howell was bootlegging again and back behind bars. After that, like so many blues and country artists of the 1920s, Howell vanished from view. In the 1960s he recalled giving up music altogether once Eddie Anthony passed away in 1934.

Howell worked odd jobs and seems to have continued to elude the census takers in 1930 and 1940. The Atlanta City Directory has him, and wife Bessie, living at the “rear” of 316 Martin Street SE in downtown Atlanta, and in 1937 at a wood yard at 21 Keystone Alley (a street which appears to no longer exist). In 1944 he is back inside, convicted of two counts of what looks like- based on the crime abbreviations used in the register- violation of liquor laws. He received a year’s sentence. The 1960 directory has Howell, with no wife, at 683 Cooper Street SW, about a mile south of today’s I-20 through the city center.

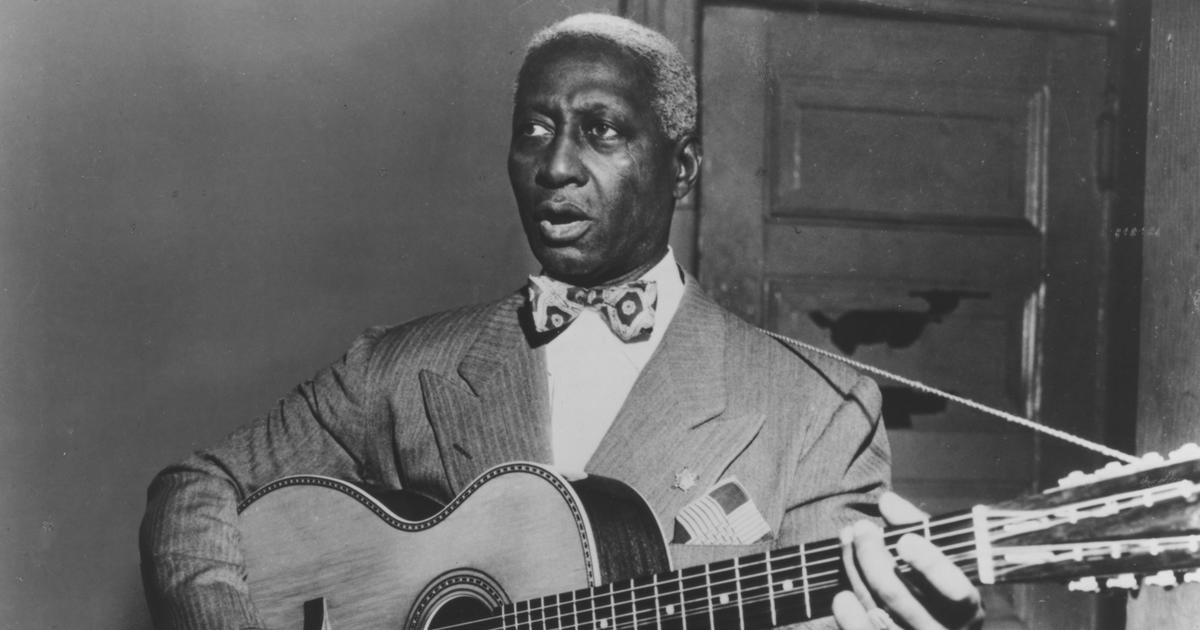

When blues enthusiasts George Mitchell, Roger Brown and Jack Boozer tracked down Howell in 1963, the old man was living in much reduced circumstances. Pitifully, he’d lost his other leg to diabetes. He was pleased with all the attention, and gathered enough strength to record a few tracks for a Testament LP, but was too sick and immobile to get any further benefit from the blues revival. Joshua Barnes “Peg Leg” Howell died 11 August 1966, aged 78 and is buried in Chestnut Hill Cemetery in Atlanta.

Joshua Barnes Howell in 1963 aged 75. Photograph by George Mitchell.

A Social Security record from 11 May 1966 contains the only reference I have been able to find to Howell’s parents, who are named as Thomas Howell and Ruth Mirik. These names do not match the Edward and Fannie Howell living in Eatonton in 1900. A Ruth Myrick was living in Putnam County in 1880 but then the trail goes cold. There is no clear path to Thomas Howell.

Today, now recorded music is all but free, Peg Leg Howell’s recordings are increasingly well-known and appreciated, and he stands among the blues greats of the 1920s. Perhaps locked away in the Putnam county archives are more clues about Howell’s early life and family. Who were his parents? Did he have any siblings? Was “Bessie” his wife all along, or a second wife in Atlanta? What happened to her? Did they have any children?

In closing, Eatonton take note. With Peg Leg Howell on guitar, Joel Chandler Harris on fiddle and Alice Walker on mandolin, we have something special.

Old World Music Classics #24

I Hear You Calling Me- John McCormack

(Victor, 1910)

ENGLISH POPULAR SONG OF THE EDWARDIAN ERA

The worst mistake a listener can make is to judge a piece of music based on its style, era or other associations. This record, a bestseller in the Anglophone suburbs and sung by one of the most famous singers of the first half of the 20th century, intrigues me for the same reason any track discussed on this site intrigues me- a striking performance, a creative composition, and a record lost to time.

I came across this record, in the over-stuffed racks of Haggle Records in Islington, on an old LP chronicling some of the earliest recordings of John McCormack (1884-1945), the Irish tenor famed for his renditions of classical arias and popular songs. I knew McCormack only vaguely and worried the combination of trained singer, parlor music and tinny 1900s technology would be bland, but the vintage of the recordings (as early as 1904) and evocative titles about old Ireland persuaded me to plump down a few pounds. I was pleasantly surprised.

Songs such as Kathleen Mavourneen and Savourneen Deelish had a mournful, heartfelt charm, carried by the eerie crackling sweetness of the small orchestra. Most of the songs were about windswept landscapes of Eire and sorrowful colleens, but one stood apart as lighter and more modern. Maybe I’m over-interpreting but on first hearing, I Hear You Calling Me seemed attuned to the tentative liberties of Edwardian London: a stolen kiss between two lovers “when the moon had veiled her light”, no mention of marriage or engagement. Perhaps playing safe, tragedy strikes. The girl dies- cause unknown but a hint of moral ambiguity- and the boy wonders if she can still behold him listening for her voice one more time. No reference to faith or God, just a longing for romance to span the grave.

The melody is fresh and inventive, yet serious and sincere. Each verse is subtly different in turn and phrasing, never mind McCornmack’s vocal acrobatics with the word “calling”. This is not trite parlor music.

I Hear You Calling Me recorded by John McCormack in 10 March 1910 in Camden NJ (Victor Records)

I Hear You Calling Me was written in 1908 by Harold Lake (lyrics) and Charles Marshall (music), and proved one of McCormack’s biggest successes. While no clue is offered in the words, the story goes that the song was inspired by a tale told to Lake about a student-teacher of 16 who fell for a girl of 15. Devoted to each other for three years, the girl then died of consumption.

What is strange to me is that Lake and Marshall- together- seem associated only with this song. Moreover, Lake was a journalist- under the name Harold Harford- not a lyricist; and Marshall was a sober 51-year old accompanist when he composed I Hear You Calling Me, not a budding songwriter bursting with youthful enthusiasm. Neither man seems a likely source for such a composition. Perhaps the last verse, which contains the beautiful line “Though years have stretched their weary length between”, is meant to imply an older man looking back on long ago events that defined his life.

Neither Lake nor Marshall merit a Wikipedia entry nor seemingly any biographical sketch, not even a photograph, save almost passing reference in connection with their famous song. No indication of year of birth or death. All we are told is that Lake took six years to come up with the words, turning them out in two minutes after recalling the sad tale of the young lovers. One source (Belfast Telegraph, 5 August 1933) says Lake showed the lyrics to publishers but was told to start again. It is not clear how Lake knew Marshall, or what Marshall brought to the composition. It is said that Marshall took the piece to McCormack’s lodging in London. The tenor was instantly enamored with it and rushed Marshall to Boosey & Co., a leading publisher who agreed to put out the sheet music. The line goes that the men made little from the score but a fortune from gramophone records.

Sheet music for I Hear You Calling Me.

Surely the authors of such a beloved song- said to be the best-selling in McCormack’s storied career- deserve better. I did some research and have been able to fill in at least some of the gaps. Birth, marriage, residence and the like reveal little about character and career but do afford some scaffolding.

Harold Harris Lake was born in Southampton, Hampshire, in May 1882, son of Harris Carrington Lake and Jane Marchant. By the 1891 census, Harold’s father is absent and I have not yet been able to ascertain the cause as death or abandonment. The family are then living with Harold’s maternal grandfather, William Marchant, in Kent. In 1901, aged 19, still in Kent, Harold is named a school teacher; and by 1911 a “journalist lead writer” in Manchester in the north of England, and still living with his mother, sister (Edna) and grandfather. Based on results from the British Newspaper Archive, in the teens, alongside his journalism, Harold was a regular contributor of serialized short stories, published in newspapers up and down the country.

Harold died in London in 1933, aged 51. There was some press coverage of the man “practically unknown outside Fleet Street” who penned the words to the famous song. Some accounts state that Harold heard of the fateful lovers from a friend, but others say he himself was the forlorn boy. I think the latter is most likely. Harold wrote the words in 1907 or 1908, about “six years” after he was 19 and a school teacher. Lake relayed the tale as taking place in Canterbury in Kent, which matches his residence in the 1901 census. He did not marry until 1928, when he was 46, to Sybil Chaloner. Sybil was 16 years of age and living in Cheshire in 1911 when Harold was in nearby Manchester. Whether Harold met Sybil when she was so young, like the fabled love of his youth, is not clear. They did not marry until Sybil was about 33. There is no evidence of any children. Just five years later, it was Harold who passed away.

Charles Marshall was born in 1856 (not 1857 as the online consensus suggests) in Halifax, Yorkshire, son of John and Emma Marshall. He was the seventh of ten children. His 1871 census entry names Charles, age 15, as an “apprentice musician”. By 1881, Charles was married (in 1879) to Janet (or Janetta) Sophia Collis and living in Hammersmith in London as a “professor of music”. The couple had, by 1891, four children and Charles describes himself as a headmaster at a school in Watford. This is consistent with press mention of a Charles Marshall as a conductor and accompanist at a Watford recital in 1888. Another press report, from 1894, names a Charles Marshall as earning a pass certificate in piano from the Royal College of Music.

Then the trail goes cold. A “Chas” Marshall, apparently our subject, is named in 1901 as a visitor at the Fulham residence of Victor Buzian, another musician. There appears to be no record of Janet and the children that year. In 1911, Charles is registered as living alone in West Kensington, while Janet, and youngest child Freda, are residents in nearby Hammersmith. Both are “married” but this may indicate a separation. Perhaps Charles’ success as a songwriter- he is the subject of many glowing notices during this period- had turned his head. Another destablizing influence may have been the death of two of his brothers, in 1909 and 1911.

Charles died, aged 71, in 1927, in Hendon in north London, but there is some evidence that he lived in the United States for much of the last decade of his live. Passenger lists mention a Charles Marshall of the right age travelling to New York City in 1914 and returning in 1926. Perhaps Charles followed John McCormack to America. The tenor became a US citizen in 1917.

Lake and Marshall struggled to build on the success of I Hear You Calling Me. The Discography of American Historical Recordings lists 36 sides with Marshall as composer, but 29 of them are for I Hear You Calling Me. For Lake the figures are 24 sides featuring songs from his pen, but 22 are for the same song. According to the John McCormack discography, the singer recorded only three other Marshall compositions but returned to I Hear You Calling Me again and again. Indeed, the piece became McCormack’s signature song. After his death, his wife used the song in the title of her memoir about her husband. Some say Marshall was McCormack’s accompanist at the time I Hear You Calling Me was first recorded, but the discography only credits him as such in 1908. Press coverage refers to one or two other Marshall compositions that McCormack performed but did not record.

Some of the titles of later Marshall or Lake pieces, such as Dear Love Remember Me and I am Longing for You might be viewed as vain attempts to repeat the magic of the big hit. A 1913 review of the former song, by Lake and Marshall, sums it up: “A conventional sentimental song of no great interest”. McCormack recorded the song the same year, but it is hard to disagree with the dismissive review.

A Victor Records advertisement in The Evening Star, Washington DC, December 18 1917; and a photograph of John McCormack around the time he first recorded II Hear You Calling Me.

By contrast, testament to the power of I Hear You Calling Me, one scholar proposes inspiration for another famous Irishman, James Joyce. In the final segment of Joyce’s Dubliners, Gabriel Conroy observes his wife transported upon hearing a song. Imagining the scene a painting, Gabriel says its title would be “Distant Music”. Séamus Reilly, author of the article, conjectures that I Hear You Calling Me is the likely source of the phrase, from the song’s middle verse, and draws various other parallels between the song and story. Like the protagonist in the song, Gretta, Gabriel’s wife, is remembering her dead lover.

Not noted in the article is that Joyce and McCormack knew each other. In fact, Joyce was also a singer, and both men had been taught by Vincent O’Brien- choirmaster at the cathedral school in Dublin. Joyce was impressed by McCormack’s victory at Feis Ceoil, the Dublin singing competition in 1903. McCormack persuaded Joyce to enter the following year, where be took bronze; and the two men performed in a concert together on at least one occasion. Joyce followed McCormack’s career with interest, and remained an enthusiastic supporter. The author alludes to McCormack as “John MacCormick” in Uylsses and in Finnegans Wake (the “golden meddlist”).

Over the years, I Hear You Calling Me is routinely cited as a “millionaire” ballad, supposedly earning Harris and Lake a large sum of money. Harold left Sybil 597 pounds sterling, less than 10,000 pounds today. A tidy sum but hardly a fortune. I could not locate a comparable death notice for Marshall.

From my perspective, Harold Lake and Charles Marshall deserve our unending gratitude for bringing I Hear You Calling Me into the world. Description, in the Irish Standard, an American publication, of a 1916 McCormack performance sums up public reaction to the song. When the accompanist “struck the three tiny notes that precede the opening bars… the response:

Excerpt from the Irish Standard, January 29, 1916.

Yet in many ways the song overwhelmed the men, who received ever-less recognition as time passed. Perhaps they enjoyed the notoriety and got on with their lives, or perhaps I Hear You Calling Me was the standard they could never reattain, the fluke they could not explain or the popular obsession that obscured whatever else they accomplished. It is regrettable that so little information is available about the creators of this great song; information that would throw more light on these paradoxes. My hope is that my rough sketches may catch the attention of a living descendant who can illuminate things better. Photographs of Harold and Charles, perhaps even together- one thing I have been unable to find- must surely exist.

Old World Music Classics #23

I Believe (The Creed)- Choir of the Russian Church of the Metropolitan of Paris

(His Master’s Voice, 1931)

RUSSIAN ORTHODOX

I bought my first 78 rpm record in 1997. Already transfixed by ten years collecting LPs and CDs of vintage vernacular music from all over the world, 78s were both tantalizing and elusive. At that time I lived in central London in the UK, one of the world’s great historical recording centers and a migration magnet from every corner of the earth, but a tough place to find interesting international shellac. In the first half of the 20th century, the city lacked the large and recent influx of immigrants from far away that drove the ethnic recording boom in the United States. Numerous international and ethnic artists were brought the UK to record but the records were for export only. By the time London swelled with Caribbean and south Asian arrivals in the 1950s, the 78 was on its way out.

Searching for 78s in the UK means wading through an endless parade of dance band and easy listening discs. So often, promising shellac was borderline- an “old song”, a foreign script or something religious. And so it was, in a junk shop near Borough Market, that I happened upon this record.

Record label- “I Believe” (The Creed) by the Choir of the Russian Church of the Metropolitan of Paris (HMV, 1931).

The label had an English translation- accessible for me, but a risk that the performance was sanitized. “Under” and a named composer can betray something overly artful. And why was a Russian Church choir recorded in Paris???

For a couple of quid, I took a chance. Side 1 turned out to be astonishingly good.- haunting countertenor vocal, choir surging and falling, a hybrid of ancient chanting and modern composition.

Today’s world of streaming often renders music as mysterious as forgotten 78s languishing in an antique shop corner. Put “I Believe (The Creed)- Russian Choir Paris” into a search engine, and you get innumerable images of the label and entries on Amazon Music, Google Play, Apple Music etc. The record is everywhere and nowhere. Almost no accompanying information is provided. To the casual listener, this might have been recorded yesterday. The choir, soloist and composer are just names shuffled in the air. Seemingly the only substantive treatment available online, in English at least, is a review in Phonograph Monthly Review in 1931, when the record was first released.

So what is the story behind this record?

This 1931 recording of a Russian Orthodox Church choir in Paris is a tale of exile and schism in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution little more than a decade earlier. Developments in the 18th and 19th centuries set the scene.

France was a great fascination for many Russian nobles and intellectuals from the 1700s, spurred by Peter the Great’s push to modernize the country. French had displaced Latin as the lingua franca of Europe, and the language became a mark of sophistication among the Russian nobility. The French Revolution of 1789 scattered many French aristocrats, some of whom took refuge in Russia. Russia’s modernization preserved authoritarianism, political and religious, better than most, but still suffered its contradictions. Some reformists chose or were forced into time abroad, often in Paris. The Russian state, too, at times, regarded France as an ally to counterbalance unifying Germany and swaggering Britain. As the century progressed, French ideas were a major influence in Russia, and a burgeoning Russian community of exiles and dissidents, travelers and officials, writers and artists, settled in Paris.

The shifting relationship between church and state in Russia is another piece of context. In the eighteenth century, Peter the Great sought to limit the power of the church, replacing the ancient Patriarch with a pliant council. Many clergy swallowed the alignment of church and state, but some saw Christianity as a call for greater liberty and pushed back. Again, many dissidents regarded Paris, also swept up in the revolutions of 1848, as a beacon of religious freedom and culture creativity.

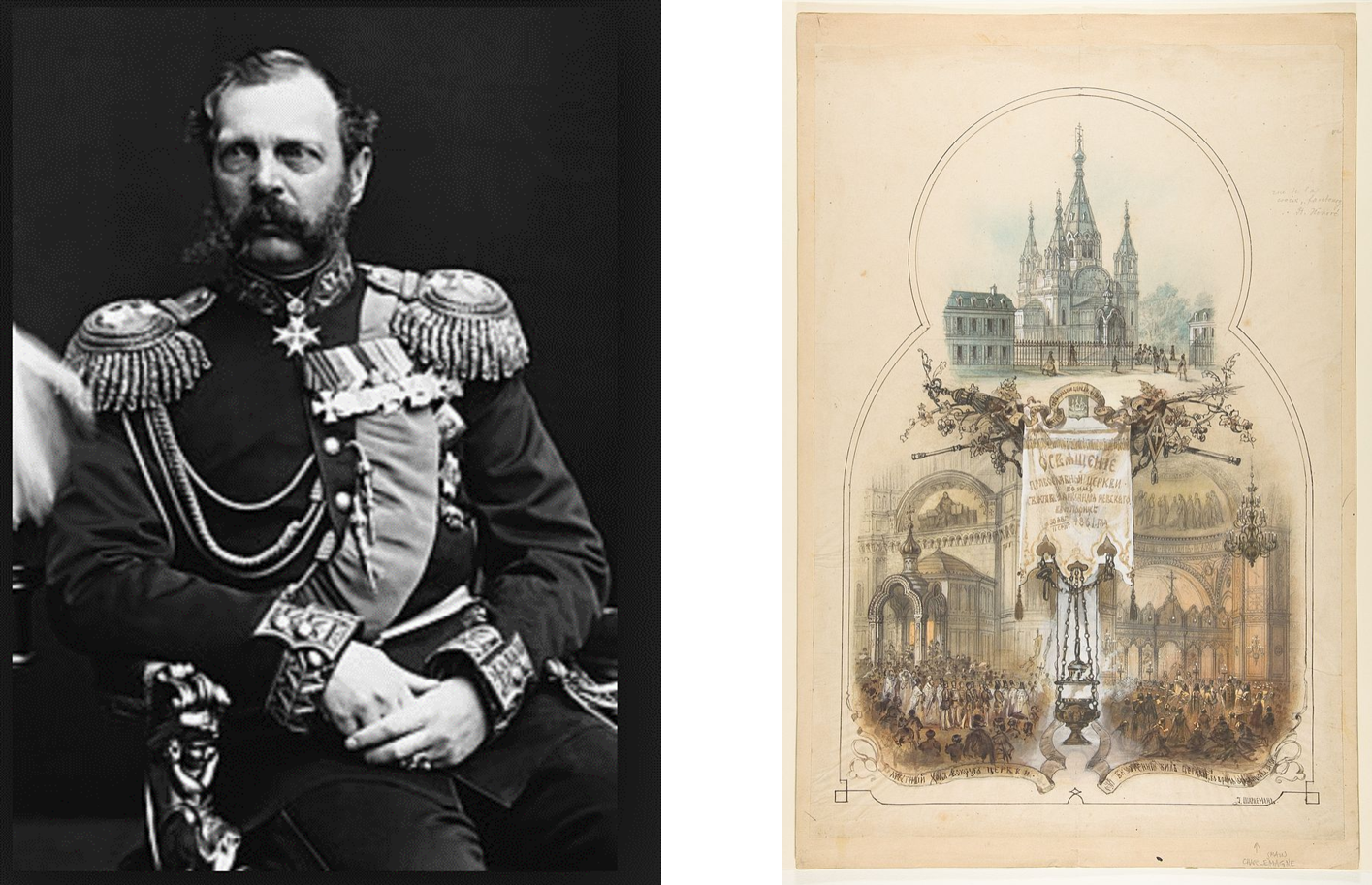

Tsar Alexander II, crowned in 1855, brought new energy to reform efforts at home. He ended the Crimean War, which pitted France and other powers against Russia, conceded captured territory at the Treaty of Paris and restored friendly relations. In 1861 Alexander took the dramatic step of freeing the Russian serfs, emancipating some 23 million people with full rights as citizens, including the right to own property, run a business and marry without permission. Alexander saw emancipation as part of his country’s commitment to being a modern nation, and as a guard against revolution.

Tsar Alexander II and the Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Paris.

The same year, in recognition of good terms between Russian and France, Alexander funded the building of a Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Paris- Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, the first formal site of Russian Orthodox worship in the country. The move was part of the Mother Church’s effort to formalize parishes for the Russian diaspora in Europe and elsewhere. Far-flung orthodoxy signaled both fragmented ideology and the makings of a globalized Russia and Russian orthodoxy, emblematic of the ambition of the state.

In 1881, Tsar Alexander was assassinated on the sixth attempt, blown up by radicals who thought the emperor was dragging his feet on further democratic reforms. But the new era that dawned, under Alexander’s son, Alexander III, and later his son Nicholas II, the last tsar, was decidedly more conservative and authoritarian. The younger Alexander and his son saw calls for reform as the kernel of their own demise, so instead framed class hierarchies as immutable and God-given. Of course, this period culminated in the 1917 Bolshevik revolution.

The Orthodox Church went from state co-opted spiritual guardian of autocracy to, in the eyes of many “godless” revolutionaries, the enemy of the people. The church itself was divided. For decades some priests had been in the vanguard of reform efforts, chaffing against official alignment of church and state, and encouraging personal exploration of faith and morality. In the early days of the Soviet era, priestly elements attempted to fashion a hybrid of socialism and Christianity, discarding the ritual trappings of traditional orthodoxy, but proved no match for the hardening atheism of the new state.

This is where Paris re-enters the picture. In 1921, the head of the ailing Mother Church, took steps to strengthen the Russian churches outside Russia, perhaps seeing the “provinces” as a haven for embattled orthodoxy. Vasili Semyonovitch Georgiyevskiy, archbishop of Volhynia in the western empire, was sent to Paris to head the ‘Provisional administration of the Russian parishes in Western Europe’. Known by his religious title as Metropolitan Eulogius, Georgivevskiy increasingly stood in opposition to the Mother Church, which in 1930 demanded loyalty to the Soviet state. Eulogius refused, in line with the views of most of his parishioners, swollen by hundreds of thousands of Soviet-era refugees who had fled to Paris in the late teens and 1920s. Eulogius, who himself had been imprisoned along with other priests in the aftermath of the Revolution, broke from the umbrella Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, which had bowed to Soviet authority, and in 1931 successfully petitioned Patriarch Photios II of Constantinople, the head of all eastern orthodox churches, to have his province recognized as independent under the patriarch’s authority.

‘I am temporarily forced to take on myself all fullness of authority…until the restoration of correct, normal relations with the supreme authority of the Russian Church’. (Metropolitan Eulogius’ letter to Metropolitan Sergius on 21 June 1930 on his reasons for ending communion with the Mother Church).

This excerpt from a 1937 interview with Archbishop Eulogius sums up the predicament of the Paris church:

Excerpt from an interview with Archbishop Eulogius, published in The Scotsman, 10 August 1937.

So, a recording in 1931 of I Believe (The Creed) by The Choir of the Russian Church of the Metropolitan of Paris sent a direct message to the Mother Church. By recording The Creed, the central orthodox prayer, Eulogius was asserting that his church carried the flame of true Russian orthodoxy. The name of the choir, seemingly innocuous, was heavy with meaning. This was the Russian Church of the Metropolitan of Paris, the center of the world.

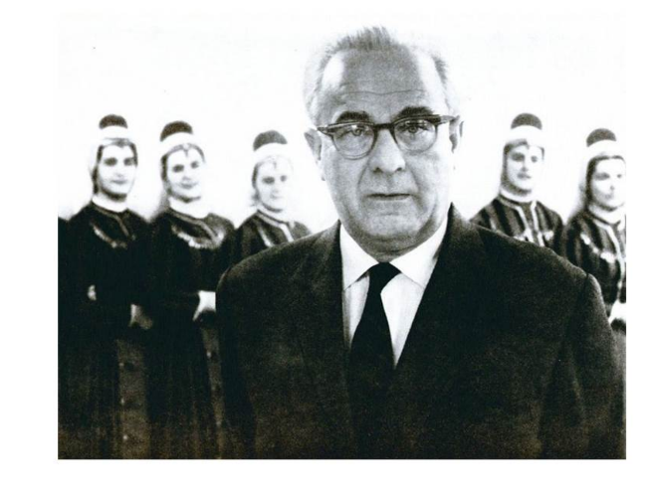

Vasili Semyonovitch Georgiyevskiy as a young priest (who would become Metropolitan Eulogius, Paris) and Alexander Gretchaninov.

The composer of this rendition of The Creed is also symbolic. Alexander Gretchaninov, renowned romantic composer of the pre-Soviet era, wrote many religious works, and impressed Nicholas II so much that we was awarded an annual pension. Gretchaninov stayed in Russia after the revolution but left for Paris in 1925, where he stayed until emigrating to the United States in 1939. No doubt Gretchaninov and Eulogius met in Paris, and the exiled composer’s piece was the perfect choice for the 1931 recording.

Immediately after World War II, perhaps seeing in Stalin’s rapprochement with England and France, and the dictator’s resort to the language of faith to galvanize the people in the depths of the conflict as signs of orthodox resurgence at home, Eulogius took his church back into the fold. He died soon thereafter, in 1946, but his successor, suspicious of Seraphim, the new Moscow Patriarch, returned to schism, as did his counterparts in many other parts of the world.

Like Gretchaninov, as the country slid into fascist orbit in the 1930s, many Russian emigres in France moved on to the United States. The vibrant Russian community, centered on Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, dissipated. But, amazingly, what today is known as the Archdiocese of Russian Orthodox Churches of Western Europe, was still separated from the Mother Church up to 2019. In 2016, the Russian Church ended communion with Constantinople when the Ecumenical Patriarchate recognized two Ukrainian Orthodox churches that broke away from the national body in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and presence in eastern Ukraine, Then, in 2018, Constantinople decided to end recognition of the Archdiocese in Paris, and integrate the various national parishes into their counterparts separately administered under the Ecumenical Patriarchate.